Refining Definitions

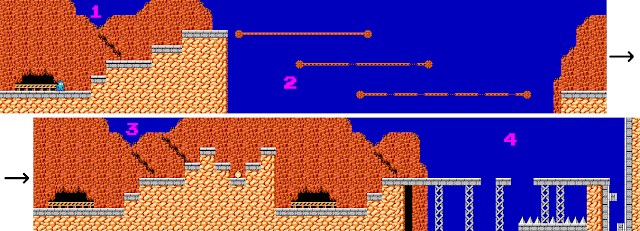

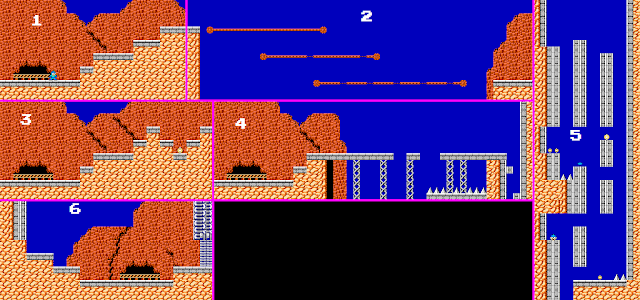

As those who have read this endeavor from the start (all three of you) will recall, my goal, or one of them, in analyzing these stages so rigorously is to break them down into their basic design elements. Now that I've got a bit of context, I think it's time to start doing that, just a bit, but first I need to get some thoughts laid out.

The 'Smallest Meaningful Unit' of Player Experience

Those familiar with philological concepts will recognize the words 'phoneme' and 'morpheme'. For those who don't, here's the basic idea: a 'phoneme' is the smallest unit of a language's phonology, or 'palette of sounds'. The specific way in which phonemes combine varies from language to language; in English, for instance, consonants and vowels combine to form syllables, which then combine to form larger units, while in Chinese or Japanese the smallest unit is already a syllable.

|

| These are phonemes, or something. Mouths saying phonemes. Do you actually 'say' a phoneme? Or is 'say' reserved for words? I mean, gurgling is a noise you make with your mouth, but you don't say someone 'said "grblgrl"', you know? Then again, the dentist does say 'Say "Ah!"', so maybe you do say phonemes. Source |

A 'morpheme', on the other hand, is the smallest meaningful unit of a language; they are the most basic elements of words that contain meaning. Some morphemes are usable words in themselves, others combine with each other to form words; to take English as an example once more, 'saw' and 'tooth' are both morphemes that can be used as words on their own, and can also be combined with each other to form 'sawtooth', a descriptive term that combines elements of both. Meanwhile, we have prefixes like 'mis' or 'un', which contain meaning ('mis' means 'wrong' or 'bad', while 'un' mean 'not'), but cannot be used on their own.

The hell am I talking about this? Well, in my experience as a player, stage design takes on similar qualities. Player experience is, after all, the be-all-end-all of game design; when you design a game, you are designing an experience in perhaps the most pure and complete way that human art affords.

Here's the thing, you see: players do not experience games tile-by-tile, but neither do they experience a stage in its entirety. Gameplay forms a continuum of experiences that separate in the player's mind by alterations in the demands the game is placing on him; that is why games whose challenges are intense but formally static (think of a Bullet Hell game like Reactance 2, for instance) can make time disappear, while games where the player must shift his activities frequently (like a classic RPG) tend to leave one's sense of time intact. A classic platformer like Mega Man occupies a space somewhere between these two; the demands the game places on the player all require responses using a fairly claustrophobic set of mechanical activities (run, jump, shoot), and yet the presence of a varied stage and enemies with different behaviors provides major alterations in the way those mechanical activities form responses.

Individual actions - a single jump across a gap, one shot fired, crossing one platform - rarely register in a player's mind if there is not some outstanding quality to distinguish them, like an unusual degree of challenge or particularly severe consequences for failure (or success) - just as phonemes do not necessarily make up a word, individual player actions do not necessarily register as a player experience. What do register are the combinations of such actions that mark the completion of larger scale challenges - jumping from platform to platform while timing shots to destroy enemies that fly up through the gaps, waiting for an enemy to lift its shield to fire off a quick shot and then jump over its attack, that sort of thing.

Consequences in Stage Design

Here's where things get a little more personal. When I attempted to make a simple platformer, I had no problems designing the engine - I gave my character the capabilities I wanted him to have and made his movement feel good to me (and I am a demanding player). My difficulties arose when I began trying to put together stages; they just felt like jumbled messes of random jumps and platforms - kind of like if a person who knew the phonemes of English but no real words started gramping notile decrosters.

|

| These are only letters in the language of Mario. And I bet you thought the language of Mario was mostly 'Woo-hoo!' and 'Momma-mia!'. Source |

There is a 'language' of stage design. This collection of meaningful design objects obviously varies from game to game, depending on the capabilities the player is given and the intended style of the game. Do you remember the article I linked to several posts ago? On game feel?

When that article talked about creating a 'gameplay garden', it was actually discussing a method for a developer to teach himself precisely that 'language' once he has decided on gameplay mechanics - to teach himself what kinds of challenges and constructions fit naturally with the mechanics and his own design goals. I am not so experienced as all that, and so I am going backwards, taking a pre-existing game series and refining specific examples of design into related categories in order to distill definitions from them. But the necessity remains the same - whether a master or a beginner, the language must be learned. Individual elements must be built into meaningful experiences.

It is because of this necessity of coming up with a larger 'unit' of design than the individual player action that the terms I have been creating all along have been on the level of player experience - challenges and choices - rather than the level of individual action. But, I don't think I've done it well enough. At the same time, I'm not sure I've got enough material yet to really refine my definitions effectively, so first I am going to finish up the levels of this game. Hopefully now anyone reading this will have an idea where I am coming from, though.